February 27, 2013

13-53

African American History: Conflict Among Black Leaders

|

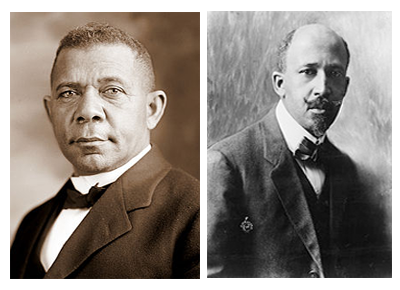

| Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Dubois |

VALDOSTA – “There is a popular misconception that all of the great pioneers and leaders throughout black history shared one common goal and always got along, but that is just not the case,” said Dr. Thomas Aiello, assistant professor of history at Valdosta State University.

Aiello is currently working on a book that explores conflict among some of the greats in African American history, focusing mainly on the rift between Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Dubois in the early 1900s.

“On one hand there was Booker T. Washington who said he was okay with segregation and focused on getting money and education into the black community,” said Aiello. “On the other hand there was W.E.B. Dubois who argued that Washington was playing into the hands of those who said that black people were inferior to white people. That’s as stark a difference as anyone could have.”

Aiello examines how Washington and Dubois went back and forth on their viewpoints concerning rights for black people.

Washington, in a speech that Dubois would later refer to as the Atlanta Compromise, encouraged black people to pursue vocational education as a means of obtaining economic security instead of striving for higher education, political office or racial equality. He referred to civil rights activism as “extremist folly” and made the statement that “In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.”

In opposition, Dubois stated that Washington was “leading the way backward.” The third chapter of his 1903 book, The Souls of Black Folk, is an essay titled “Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others.” The essay criticizes Washington’s stance and claims that it indirectly contributes to “the disfranchisement of the Negro, the legal creation of a distinct status of civil inferiority for the Negro and the steady withdrawal of aid from institutions for the higher training of the Negro.” The essay also encourages people to “unceasingly and firmly oppose” Washington’s teachings.

“During that time, one was either pro-Dubois or pro-Washington,” said Aiello. “There was no in between. This rift actually got pretty heated between the two groups. Washington hated the literature that Dubois put out, so much so that he would threaten to pull Tuskegee’s advertisements from newspapers if they ran anything written by Dubois. He would even tell white people about NAACP meetings so they could go break them up.”

The debates between the two leaders lasted until Washington’s death in 1915.

“Dubois lived far longer than Washington and continued to bash him and his teachings, and that set the debate for the next generation,” said Aiello.

Aiello added that such divides can be found throughout black history.

“In the late 1800s and early 1900s there was W.E.B. Dubois who wanted immediate integration, traditional civil rights and the rights to vote and Booker T. Washington who did not feel the need to be around white people and was fine with living separately,” he said. “If you take Washington out of rural Alabama and place him in New York in the 1950s and 60s, you have Malcolm X. While Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was promoting integration and civil rights – the same things that Dubois strived for - Malcolm X encouraged complete separation of white and black people and argued that black people were superior to white people. But if we were to go back to the mid-1800s we can still find it with Frederick Douglass, who wanted equal rights for black people, and Martin Delaney, the original black nationalist, who encouraged black emigration back to Africa arguing that black people would never have equal rights in a place where they were not the majority.”

Aiello has also pinpointed some present-day conflicts among black leaders, particularly between Dr. Cornel West and Melissa Harris-Perry. West has criticized Harris-Perry and Rev. Al Sharpton for their support of President Barack Obama, who he feels has turned his back on black people. Harris-Perry has also responded to one of West’s addresses by referring to it as a “self-aggrandizing, victimology sermon deceptively wrapped in the discourse of prophetic witness.”

“The divide still exists,” said Aiello. “There is plenty of argument in the black community about better methods to conquer problems and what needs to come first. However, there is really no right answer to what needs to be resolved first. What it all boils down to is that there is still a state of racial inequality that exists although the barriers are far more subtle now. There are ways of racially discriminating without being overtly racist and it just leads to a lot of debates on how to go about tackling that.”

Aiello, who has studied African American history for more than 15 years, said he is often asked why he - a white man - chose to make African American history his focus.

“I grew up in a racist place in northeast Louisiana and went to an all-white high school,” he explained. “My parish has had more lynchings than any place on earth. As a child that did not seem weird to me although my family always taught me to be accepting of all races and cultures. However, sometime between going to college in Arkansas and returning home, I actually realized how different my hometown is from other places. Even if you’re taught not to hate others, you cannot avoid witnessing it in places like my hometown. It gets to you and you want to understand it and figure out why it has the problems it has, and eventually you find all of the problems go back to race.”

Aiello said that the topic of race interested him and seemed important.

“Of course there were other topics and careers that seemed interesting to me, but they were not important,” he said. “Race in the South is important and it has consequences that we can actually see.”

Aiello has taught at VSU since 2010 and led classes that focus on the economics of slavery, black political murder, the Harlem Renaissance and the black power movement. He currently teaches courses on black press and the second half of African American history.

“I encourage my students not to just celebrate African American history, but to understand it,” Aiello said.

Aiello has written and published several books that focus on athletes in African American history and Jive. His books are available at Amazon.com.

Valdosta State University’s 2013-2019 Strategic Plan represents a renewal of energy and commitment to the foundational principles for comprehensive institutions.

Implementation of the plan’s five goals, along with their accompanying objectives and strategies, supports VSU’s institutional mission and the University System of Georgia’s mission for comprehensive universities.

The story above demonstrates VSU's commitment to meeting the following goals:

Goal 1: Recruit, retain, and graduate a quality, diverse student population and prepare students for roles as leaders in a global society.

Goal 3: Promote student, employee, alumni, retiree, and community engagement in our mission.

Goal 4: Foster an environment of creativity and scholarship.

Goal 5: Develop and enhance Valdosta State’s human and physical resources.

Visit http://www.valdosta.edu/administration/planning/strategic-plan.php to learn more.

Newsroom

- Office of Communications Powell Hall West, Suite 1120

-

Mailing Address

1500 N. Patterson St.

Valdosta, GA 31698 - General VSU Information

- Phone: 229.333.5800

- Office of Communications

- Phone: 229.333.2163

- Phone: 229.333.5983